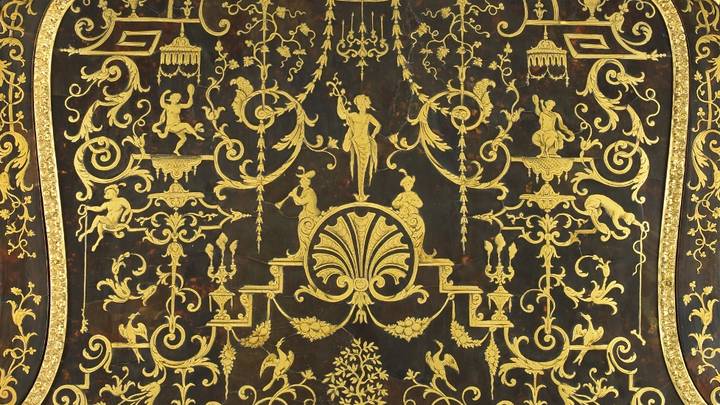

A study of the materials used by André-Charles Boulle (1642-1732) is limited by the fact that there are few written sources that describe his creative process, despite the relatively large number of pieces of furniture identified today as coming from his workshop.

One of the most important sources connected to Boulle and his workshop is a deed of relinquishment: in this document, dated 6 October 1715, Boulle transferred his workshop to his sons.

In the process, an inventory was drawn up of the workshop’s contents, which unfortunately mentions very few materials: essentially it only includes some indigenous and tropical woods.

It mentions, for example, boards of oak fir and walnut, cherry and ‘Norwegian wood’, sections of an undefined ‘yellow wood’, some ash, half logs of ebony, red or sandalwood, a few pieces of wood from Stettin, boxwood, barberry, holly and brazilwood.

Surprisingly, brass, pewter and turtleshell – the materials Boulle used for his marquetry inlays – are not mentioned anywhere in the inventory.

In view of the above, it appears that the woods, paticularly the high-quality oaks, would have come from Norway and Poland, passing through the town of Stettin on the Baltic coast. Curiously, archaeodendrometrical analyses on the oak used in Boulle furniture have shown that they came primarily from French forests.

Further technical studies of the corpus of furniture attributed to Boulle has shown that, in the case of pieces produced at the end of the 17th century and the very beginning of the 18th century, fir was used predominantly in the construction of the furniture. On some occasions, mulberry wood was used as well, a timber which is naturally yellow-gold in colour.

This analysis was carried out, for example, on the pedestal cabinets preserved in the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Musée du Louvre. Both of these examples were made by Boulle around 1690 and contained mulberry wood.

It is possible that this is the mysterious ‘yellow wood’ referred to in the 1715 deed of relinquishment, especially as it is mentioned separately from the only other yellow wood mentioned in the inventory, which went by its vernacular name of ‘barberry’.

We should also mention here the two chests of drawers delivered in 1708–9 to Louis XIV's bedroom in the Grand Trianon, which feature drawers made of Indian coralwood, or pteropcarpus indicus, a wood used uniquely for this commission by Boulle, thus lending a particularly precious character to the furniture. The pair is now kept at the Château de Versailles.

The use of coloured woods as veneers was also common in Boulle's production. Alongside the previously mentioned boards, the 1715 workshop inventory noted the presence of numerous coloured woods in thinner sheets.

A technical study of wood veneers on Boulle furniture has shown he, for example, used black ebony, or diospyros ebenum, which is sometimes combined with another dark, veined wood now called ‘Mozambique ebony’, or dalbergia melanoxylon.

Another example of an exotic wood identified in Boulle furniture is red ebony, or macacauba trebol, which can easily be confused with amaranth because of its purplish colour. It can be seen, for example, on the tops of pedestal cabinets in the Louvre and was regularly used in French furniture production up until the 1730s.

Other coloured wood veneers used by Boulle in his marquetry are described in the deed of relinquishment of 1715 and can be identified on the floral marquetry wardrobe made around 1690 in the Musée du Louvre. These include coralwood, brazilwood, maple, holly, boxwood, green ebony, yew and barberry.

The Louvre wardrobe was studied during its restoration at the C2RMF. Highlighted through X-ray fluorescence analysis, the marquetry woods used to make the vases containing the floral bouquets, the garlands and the bases of the vases, all showed the presence of copper- and iron-based pigments.

Boulle used these to obtain green and blue colours on the veneered woods, but also to create, very probably, silver colours on the base. Boulle also made considerable use of pigments behind his turtleshell marquetry, applying pigments, such as blue, red and black, to paper and placing these behind the veneers. These techniques gave him the opportunity to create furniture with dazzling colour schemes.

This article was written by Marc-André Paulin, Head of the Furniture Conservation Workshop at the Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France.