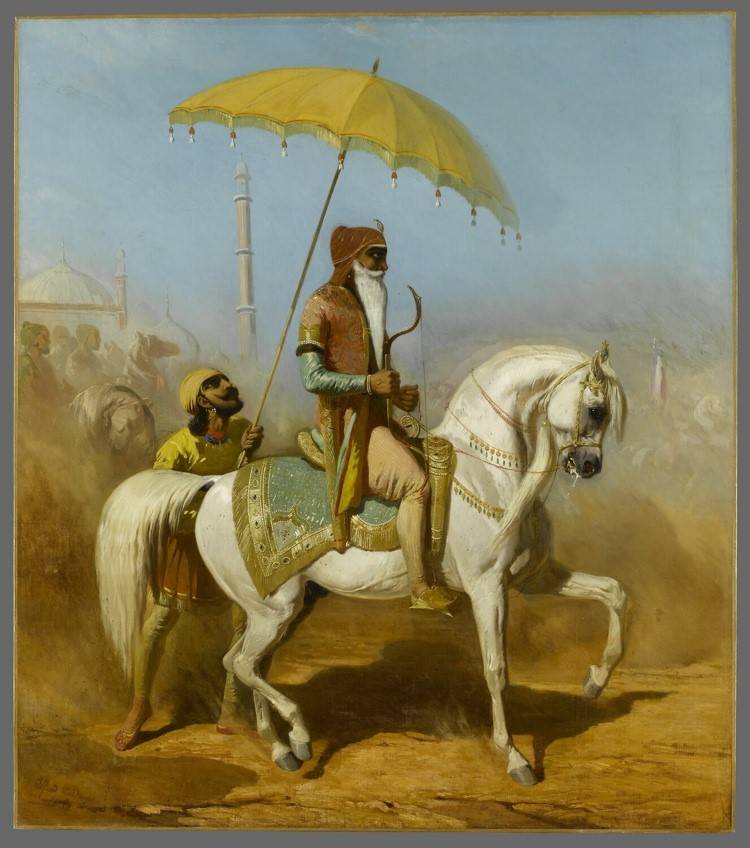

By the end of the 18th century, the factious Sikh confederacies were ripe for consolidation, but that task would require exceptional diplomacy and military power. Despite Ranjit Singh’s (1780-1839) unimpressive (some thought repugnant) visage and stature, he towered above the warring misls (confederacies) in ambition and ruthlessness.

At the age of five, he had lost vision in one eye to smallpox; at ten, he lost his father. After taking command of his late father’s confederacy, the young Sikh was determined to become an accomplished warrior and leader. His teenage years were spent cultivating his martial instincts. According to the irregular cavalry officer, Colonel James Skinner (1778–1841), a contemporary who was also one of his earliest biographers, Ranjit Singh

took great pleasure with the daily supervision of the army, the search for horses and fine warriors, and the pursuits of musketry and horse riding […] He was entirely preoccupied with practicing his skills with javelins, swords, muskets, and continually drilling the army.

A British officer would later learn about Ranjit Singh’s simple but effective philosophy vis-à-vis leadership in the field:

His personal bravery is such, that he frequently leads on his storming parties, and is the first man to enter the breach. […] he is a fatalist which gives additional energy to his natural courage. He says it is vain for a man to attempt to hide himself, since whatever is doomed to be his end must inevitably happen, as pre-ordained.

Ranjit Singh’s early career benefitted from important marriage alliances, and his first to Rani Mahtab Kaur effectively united two previously warring Sikh confederacies.

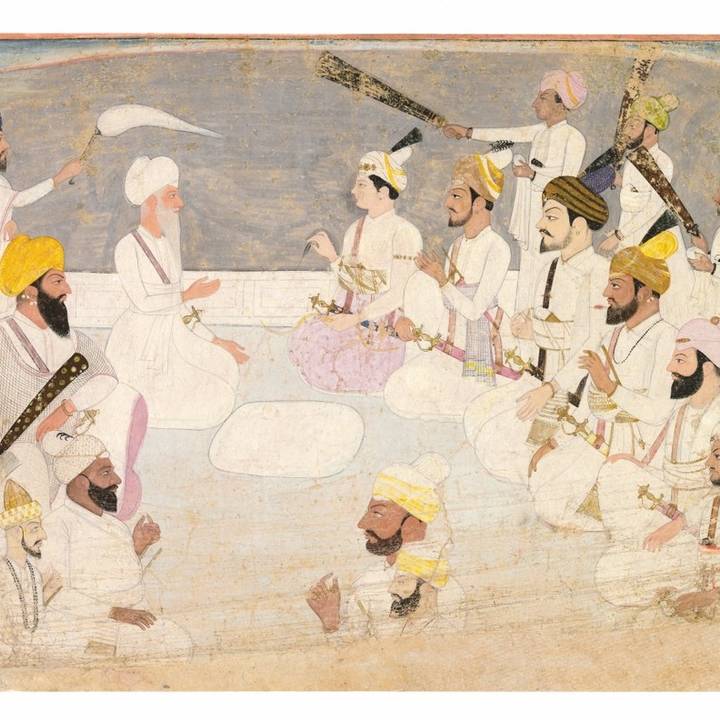

With the military resources of his powerful mother-in-law, Rani Sada Kaur (1762–1832), and the endorsement of Sahib Singh Bedi (1756–1834), a descendant of Guru Nanak, Ranjit Singh embarked on a remarkable military career of conquest and territorial expansion.

At the age of 19, he forced Zaman Shah (1767–1845), the king of Afghanistan and Ahmed Shah Abdali’s grandson, to bestow a grant of Lahore, which he then seized by force in 1799; two years later he was anointed ‘maharaja’ (great king) of the Sikhs by his Bedi mentor; and at the age of 22 he annexed Amritsar, thus becoming master of Punjab’s two most prosperous cities.

Ranjit Singh was relentless in his pursuit of kingship. In the process, he terrorised nearly all the other Sikh misls into submission; elderly patriarchs were killed, and their widows, military resources, property and populace subsumed into his own.

By 1820, the conquered territories of Punjab between the Indus and Satluj rivers, and further north over much of Jammu and Kashmir, lay at Ranjit Singh’s feet. He had achieved this with an indigenous army manned by Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims. However, to counter the territorial ambitions of the British East India Company on his southernmost border, Ranjit Singh began to employ the expertise of commanders who had previously served in the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte, the defeated French Emperor, to oversee the transformation of a significant part of his forces into a largely Europeanised army capable of matching any looming threat.

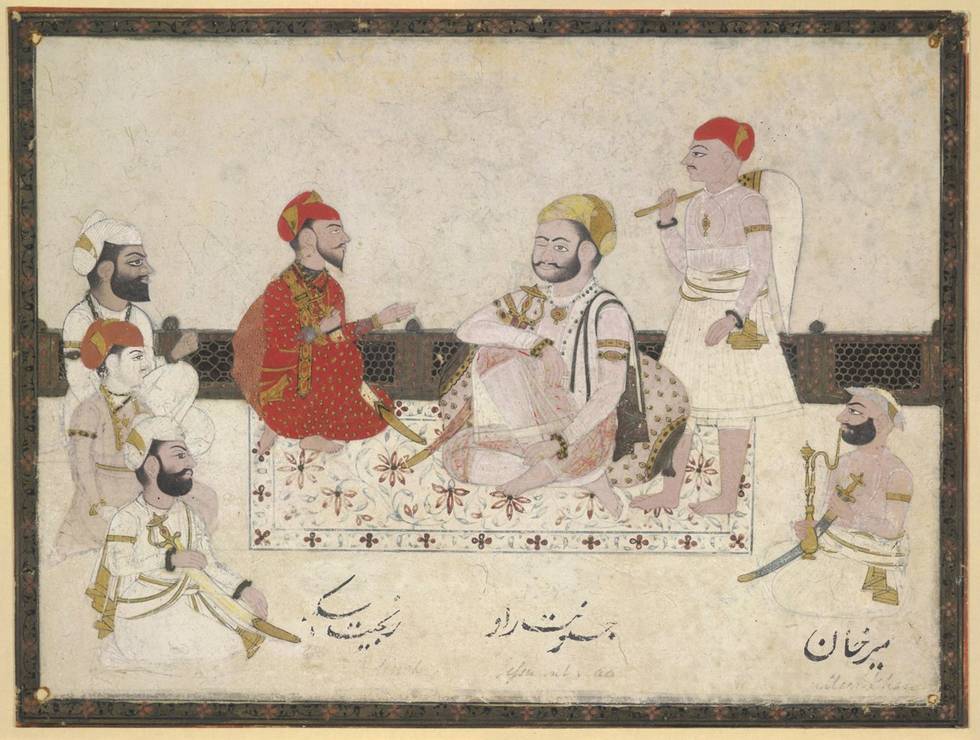

The Sikh maharaja received a wide range of Westerners into his court, enlisting Company deserters, mercenaries and medical men from across Europe and as far away as the United States of America. The multifarious soldier-adventurers were enticed by the chance to make their fortunes and to escape their previous circumstances. Each had to demonstrate their worth and allegiance to the Sikh ruler before appearing on his payroll.

At its zenith, Ranjit Singh’s reorganised army was an unparalleled example of ostentatious pageantry on the parade ground, and brutal effectiveness and pinpoint precision on the battlefield. During Ranjit Singh’s reign, this army did his bidding – it kept at bay any British, Afghan or Russian threat for four decades and solidified the borders of a rich and resourceful empire the size of modern-day Germany, which had at its epicentre the lavish royal court within the imperial walled city of Lahore.

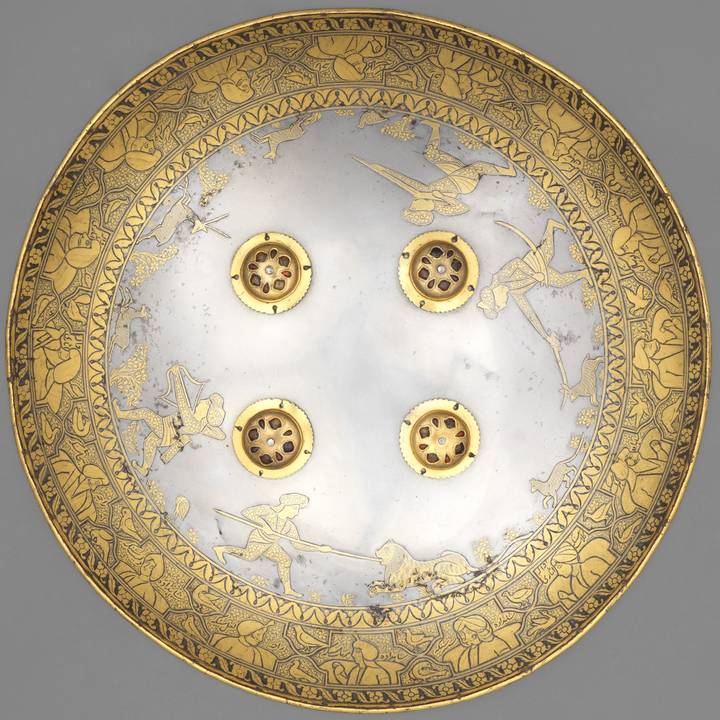

European visitors to Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s dominions often marvelled at the staggering opulence of his cosmopolitan royal court at Lahore. Although his career was marked by an almost obsessive preoccupation with conquest and the accumulation of precious stones (including the fabled Koh-i-Noor diamond), majestic horses, jewelled swords and exquisite shawls, Ranjit Singh’s appearance was notoriously plain compared to his spectacularly robed courtiers.

Though unlettered, Ranjit Singh possessed a prodigious memory and organisational abilities that allowed him to run his empire. From peace and war to finances and diplomacy, he was the master administrator, financier, spymaster and legislator of his kingdom. His reign established a cosmopolitan empire that brought about a golden age where trade boomed and the arts flourished.

By the end of his life, Ranjit Singh’s empire encompassed the former Mughal provinces of Lahore, Multan and Kashmir, and beyond into Ladakh in the north and Afghan territories to the west, bringing an unprecedented era of peace in a region that had been wracked for centuries by unrelenting invasions. Within a decade of his death, the empire collapsed and many objects from his treasury were taken to Britain, and are now in national collections.

This article was written by Davinder Toor, co-curator of Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King.