The Background

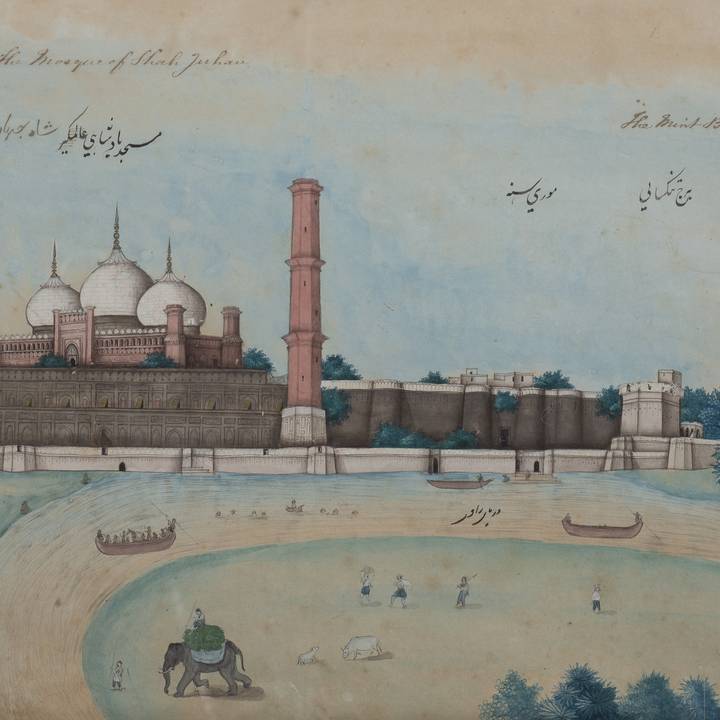

Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780-1839) had extended his control over much of the Punjab by the turn of the 19th century, making the city of Lahore his capital in 1799. Looking to prevent the British East India Company’s expansion north of the Sutlej River, which marked the border between the two powers, he rapidly modernised his army. Officers from France, Italy and other European countries, as well as the United States, were welcomed and employed to train his troops. Western artillery was copied and improved upon. By 1839, the year of his death, he had built an impressive arsenal comprising of more than 500 pieces, including siege guns, which could rival that of the British.

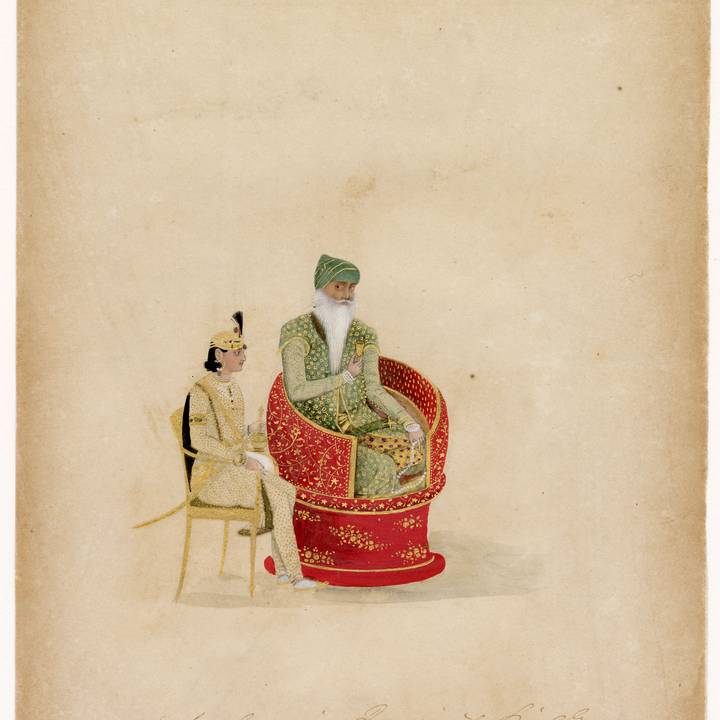

However, his death initiated a series of assassinations and succession struggles. By late 1845, Ranjit Singh’s youngest son, the seven-year-old Duleep Singh (1838-1893), was sitting on the throne while his mother, Maharani Jindan Kaur (1817-1863), had become the effective regent. Alongside her was Lal Singh (d. 1866), the new prime minister and Tej Singh (1799-1866), the commander of the army. The real power however lay with the increasingly powerful Sikh army councils or panchayats – without whose support no decision could be taken and who had raised and overthrown whom they wished during the bloody struggles following Ranjit Singh’s death.

The Causes

Across the Sutlej River, the East India Company saw opportunity and pretext in the political instability at Lahore, and the possibility of expanding control to the borders of Afghanistan proved irresistible. Measures were taken to increase British strength at Ferozepur, the British garrison stationed on the Sutlej. Supply depots, stretching from Delhi to the borders of the Sikh state, were also built to facilitate an advance into the kingdom as and when desired. Various portions of Lahore territory south of the Sutlej were annexed causing anger in the Punjab.

In Lahore meanwhile, the Sikh government decided a war would be advantageous too If they defeated the East India Company forces, their issues with the army would be resolved and the panchayats would be occupied in battle, away from Lahore. On the other hand, if they were defeated, they would be rid of the army committees entirely. Both Lal Singh and Tej Singh had no reservations about a British takeover if their positions were confirmed in a subservient role. War therefore seemed favourable to both sides.

The First War (1845–46)

The First Anglo-Sikh War broke out on the 11th of December 1845 with the Sikh army crossing the Sutlej River, which marked the border between the two powers. The first battle, at Mudki, was inconclusive. The British force was led personally by the commander-in-chief, Sir Hugh Gough (1779-1869), who pushed back an advance portion of the Sikh army, without gaining a significant victory. On the 21st of December, the two armies met at the small village of Ferozeshah. After some initial success, the British force was pushed back with defeat looking imminent, as ammunition and shot had been completely exhausted. The governor-general, Sir Henry Hardinge (1785-1856), who was present at the battlefield, burned his private papers during the night in anticipation of a surrender on the following day. However, a Sikh retreat ordered by their commander Lal Singh, saved the British forces. Another Sikh army under Tej Singh, which was arriving at the battlefield, was also ordered back. At the battles of Aliwal and Sobraon, the British gained conclusive victories. In the subsequent Treaty of Lahore, a British resident was imposed on the state, although Maharaja Duleep Singh remained the nominal head.

The Second War (1848–49)

The Second Anglo-Sikh War broke out two years later. Similar to the first war, two inconclusive battles were fought at Ramnagar and Sadulpur, before the armies clashed at Chillianwala. Fought in a dense jungle and at night, the British line was repelled and they retreated in confusion with heavy casualties. However, Sher Singh (1807-1843), the over-cautious Sikh commander, failed to take advantage and order an advance. Sir Hugh Gough, the British commander-in-chief, would be removed from his post for this near catastrophe, but he managed to secure a conclusive victory at Gujrat before his replacement arrived. Following the surrender of the Sikh army after Gujrat, the annexation of the Punjab was announced on the 29th of March 1849.

The Aftermath

Maharaja Duleep Singh was deposed and given a British pension; a Board of Administration, which included Sir Henry Lawrence (1806-1857) and his brother John Lawrence (1811-1859), formed the government of the newly annexed territory. Veterans of the Sikh army meanwhile were welcomed into the Company’s forces and would play an important part in the Indian Uprising of 1857, only eight years later.

This article was written by military historian, Amarpal Singh Sidhu, author of The First Anglo-Sikh War and The Second Anglo-Sikh War.