In March 1822, a Lahore newswriter reported that two strangers, ‘Ulur’ and ‘Wuntoor’, had arrived in the Sikh capital. They were clearly Europeans and initially it was suspected that they were British spies, seeking employment for nefarious reasons. But neither Allard nor Ventura was British. Indeed, both had spent much of their lives fighting against British interests.

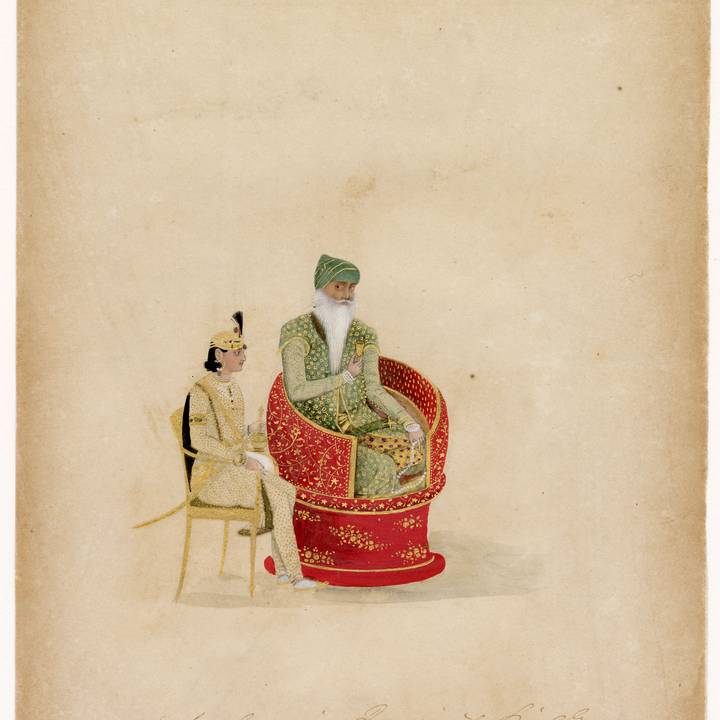

They would become the first of Ranjit Singh’s (1780-1839) Firangis, a term derived from ‘Frank’ but adapted in Indian usage to mean ‘foreigner’, especially of European descent. Collectively they gave rise to what was almost certainly the most cosmopolitan court in the world at that time.

Jean-François Allard (1785–1839) was in fact an adventurous former sergeant-major of Joseph Bonaparte’s bodyguard and a recipient of the Légion d’honneur. His friend Jean-Baptiste Ventura (1794–1858), meanwhile, was from an Italian Jewish family, born in the Duchy of Modena. He had also fought for Napoleon, in his case against the Austrians in Italy in 1814. When Napoleon’s Grand Armée was disbanded, both men had set off east in search of excitement and employment.

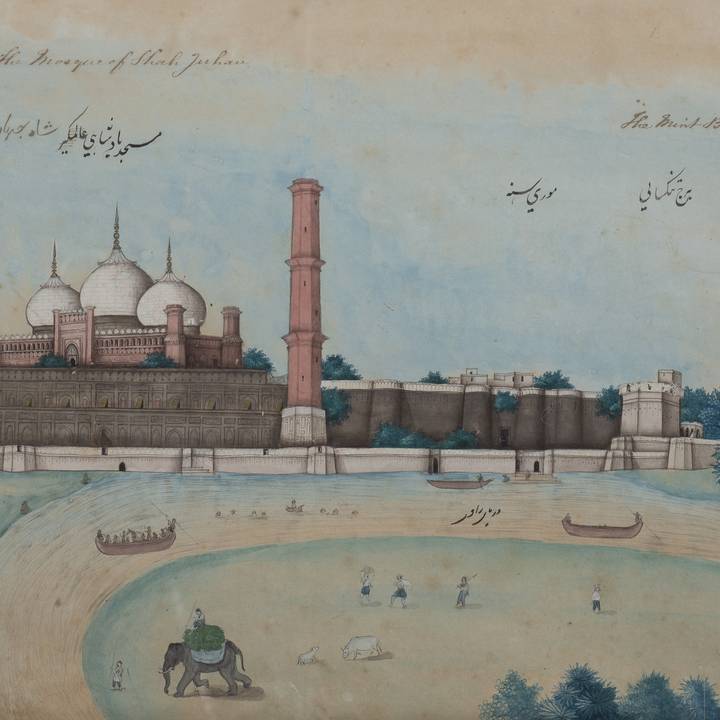

They made a perilous crossing of Afghanistan, emerging down the Khyber Pass into the territories of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. By May they had established the truth of their credentials. By June, British spies were picking up rumours that the maharaja planned to use them to seize Peshawar and Kabul from his Afghan enemies.

Ranjit Singh’s power rested principally on his remarkable 85,000-strong army, the Sikh Khalsa. At the very beginning of his reign, in the opening years of the 19th century, the first regular regiments in this army came mainly from the remains of the Maratha mercenary brigades of Hindustan, which had been defeated and disbanded by the British East India Company in 1803. They also incorporated a growing number of British deserters from the armies of the Company. Later, Ranjit Singh started raising a regular artillery that was cast and manned by specialists who had also worked for the Marathas. By 1809, there were 1,500 European-trained infantry out of an army of 24,000 in the armies of the Khalsa.

The arrival of two Napoleonic veterans presented the perfect opportunity to upgrade and modernize this military force by commissioning them to add an elite corps, the Fauj-i-Khas. Not only would it aid internal stability; it would also provide extra preparedness for any external threat posed by Afghan warlords to the north-west and the formidable Company to the south. Armed and trained on the latest Napoleonic model, it was officered by a growing group of French and Italian Napoleonic veterans who had followed in Allard and Ventura’s eastward footsteps. Foremost were Claude Auguste Court (1793–1880), a graduate of the Saint-Cyr military academy from Grasse, who had fought at Leipzig, and Paolo Avitabile (1791–1850), a dashing Italian artilleryman from the Amalfi Coast.

These Firangis were bound by several conditions of service under Ranjit Singh. Most importantly was the promise of fidelity to the Sikh Empire, even if it meant going to war against one’s own countrymen. They were also to abstain from eating beef and smoking in public. Another stipulation was to marry locally.

By the end of 1822, under the tutelage of Allard and Ventura, the Fauj-i-Khas had begun its growth to five entire regiments, 15,000 strong. In 1833 a third of the troops in the Punjab were under the control of the Firangis, and were known locally as Francisi Campu, the French Legion. Ranjit Singh was so impressed by the performance of these modern infantry regiments that he decided to reorganize his entire army on this basis. The Fauj-i-Khas would eventually contain officers from France, Spain, Germany, Romania, Russia, Italy and Greece, as well as troops from the Indian territories under the control of the East India Company. Many of the Firangi generals doubled as military governors of important frontier provinces. Avitabile, for example, was a notably brutal governor of Peshawar between 1838 and 1842.

Another was Alexander Gardner (1785–1877), an American-Scottish adventurer, who took service as a colonel of artillery in Ranjit Singh’s army. Here he fought against the Afghan emir Dost Mohammad and went on to play an often pivotal role in the succession struggles which followed Ranjit’s death. As the Sikh Empire disintegrated, Gardner was often a witness and usually a participant in much of this violence.

As long as Ranjit Singh was still in charge, the Sikh Khalsa remained allied to the East India Company, and in 1839 they engaged in joint operations against the Afghans at the outbreak of the First Anglo–Afghan War. The British generally got on well with Ranjit Singh, but they never forgot that his army was the last military force in the subcontinent that could take on the Company on the field of battle.

As a result, the Company had discretely stationed half its Bengal army, totalling more than 39,000 troops, along the Punjab frontier. They were right to be wary: in the Anglo–Sikh Wars, the Fauj-i-Khas came close to defeating the massed armies of the Company. Today their cannon can still be seen lined up in the unlikely final refuge of the lawns of Chelsea Hospital, where they were brought as trophies after the Sikh defeat of Chillianwala in 1849. Thus, within a decade of their deaths, the empire so brilliantly established by Ranjit Singh and diligently served by General Allard was lost forever.

Text adapted from William Dalrymple’s chapter ‘Firangis’, in Toor, D. Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King, London, 2024, pp. 89-95.