The arms and armour held at the Wallace Collection amount to almost half of the museum’s holdings, with close to 1,000 items originating from beyond Western Europe. With around 40 being from Punjab, they include some of finest examples of Sikh weapons in a public collection.

The early formation of the collection began with the 4th Marquess of Hertford (1800–1870), an avid collector whose fortunes derived largely from estates in England and Ireland. While he is most well-known for his tastes in 18th-century French paintings and decorative arts, he also amassed an important collection of Middle Eastern, Ottoman and Asian arms and armour – an interest he only fully developed in his later years.

As a young man in his twenties, the 4th Marquess had spent some time attached to ambassadorial circles in Constantinople, an experience which perhaps informed his later life’s passion. Residing mostly in Paris, he was also swept by the growing fascination for the ‘Orient’, which had been fuelled by French military campaigns in Egypt (1798–1801) and Algeria (1830). In this context, the ‘Orient’ was a catch-all term that included the vast and disparate regions of the Middle East, North Africa, Turkey, Greece and Asia.

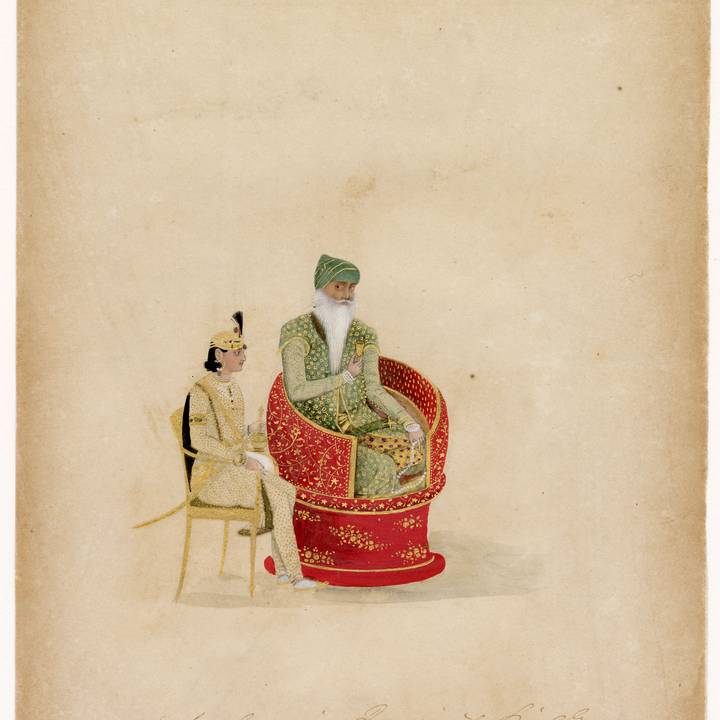

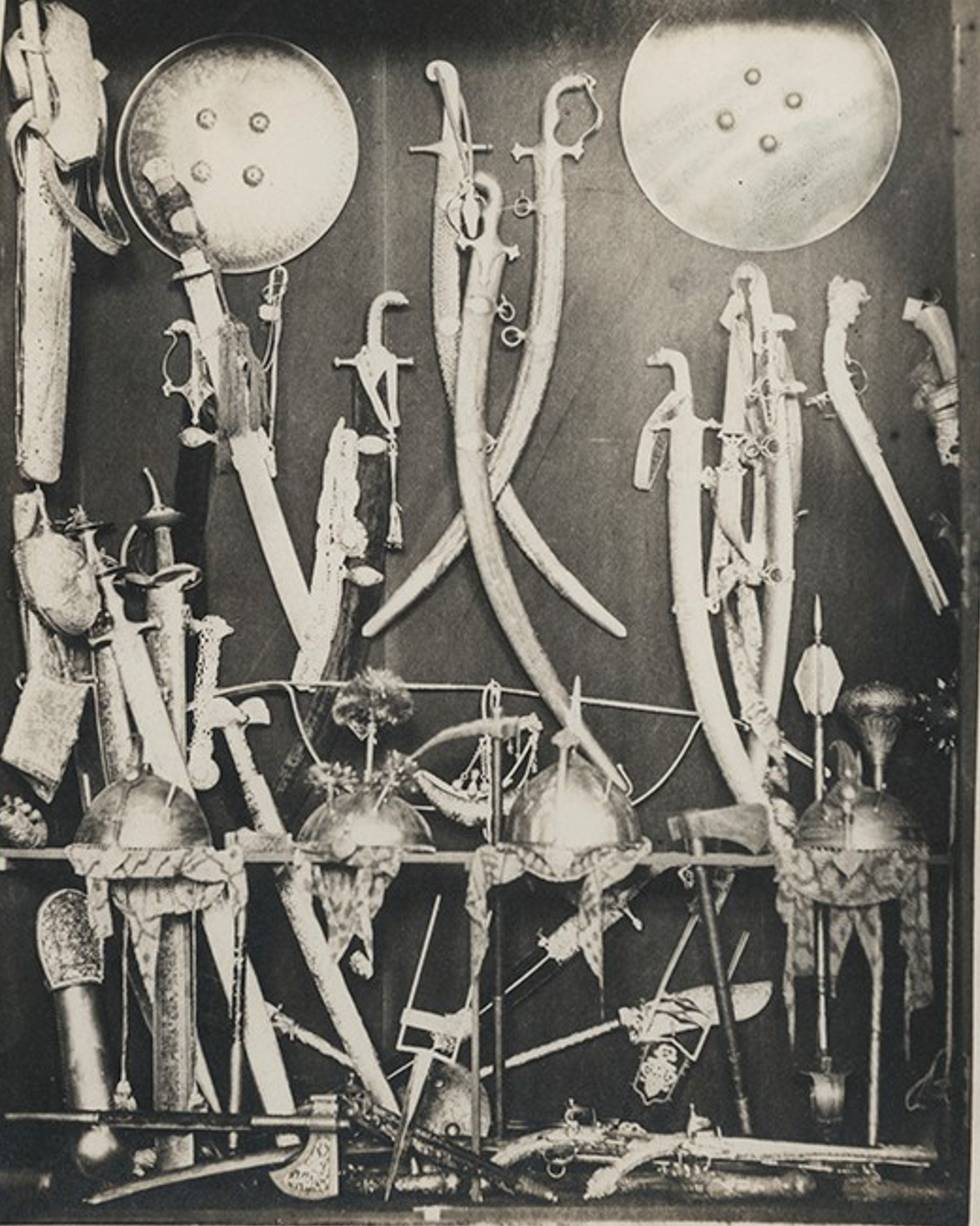

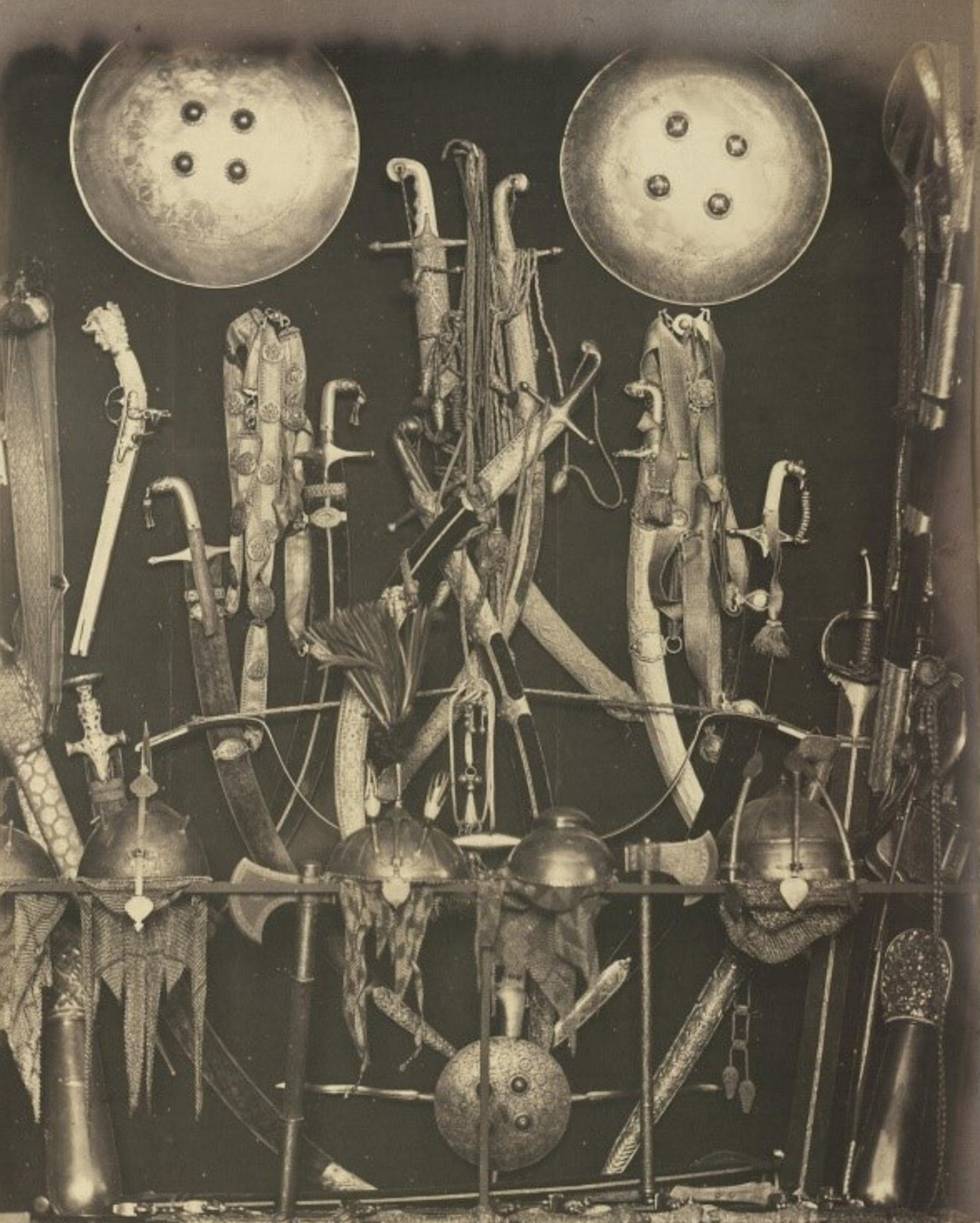

In 1865, the 4th Marquess lent 160 pieces of non-European arms and armour to the Musée Rétrospectif in Paris. The surviving exhibition catalogue, together with a few photographs, provide a glimpse into his collection at that date. Amazingly, these images include three highlights from the Wallace Collection’s Sikh holdings: a sword described in the 1865 catalogue as having belonged to Ranjit Singh (1780-1839) (OA1404), a Sikh turban helmet (OA1769) and a shield bearing portraits from the Lahore court (OA2188).

A sword associated with the Sikh maharaja might have held a special allure to the 4th Marquess, who was always keen to acquire items related to the important personalities of the day. He was also a great admirer of Napoleon, many of who’s former officers eventually found employ at Ranjit Singh’s court, dubbing their new leader the ‘Napoleon of the East’.

After the death of the 4th Marquess, his likely illegitimate son, Sir Richard Wallace inherited his father’s collection, which he subsequently shaped with his own additions.

Wallace moved to London in 1871 and a room on the second floor of Hertford House was chosen to display his ‘Oriental Armoury’, as it was then referred to.

In 1897, Wallace’s widow bequeathed the works of art in Hertford House – including the arms and armour - to the nation. The items in the former ‘Oriental Armoury’ now encompass the Wallace Collection’s Arms and Armour I Gallery.

Unfortunately, acquisition records for the Sikh arms and armour collections are not extensive. It is important to remember that these materials were not traded as ‘fine art’, many being near contemporary in date when they were purchased.

Nevertheless, we know that the 4th Marquess and Sir Richard Wallace acquired extensively at auction and from dealers in Paris and in London, both cities being major markets for the trade.

The Parisian art market benefitted from returning ex-Napoleonic officers, who had served in the Sikh Army under Ranjit Singh. Gifts of arms and armour were often presented by the maharaja to his generals, who later sold them on the open market. For instance, a Parisian saleroom saw a major sale of arms and armour in 1855, when the collection of General Ventura was placed at auction.

19th-century collecting trends for South Asian arms and armour were very much influenced by widening colonial expansion, which increased both the availability of items and public awareness of them. The forced disarmament of the Sikh army following the Second Anglo-Sikh war (1848–49) also resulted in an influx of arms to European markets with returning military officers.

Reports of the two Anglo-Sikh Wars had circulated widely in the press and the valour of the Sikh army had been repeatedly lauded. Public interest was further sparked by the Great Exhibition of 1851, one of its star attractions being the famed Koh-i-Noor (‘Mountain of Light’), thought at the time to be one of the largest diamonds in the world. It had been seized from the Lahore Treasury (toshakhana) and displayed at Crystal Palace, along with examples of Sikh arms and armour that were sold at auction the following year.

Upon the annexation of Punjab by the British East India Company (EIC) in 1849, the Treaty of Lahore proclaimed that ‘all the property of the State, of whatever description, and wheresoever found, shall be confiscated to the Honorable East India Company’. This entailed the detailed inventorying and valuing of the entire Lahore Treasury. From the carefully recorded lists, only a selection of state jewels and jewelled weapons were kept for Ranjit Singh’s last successor, his youngest son, Maharaja Duleep Singh (1838–1893).

Of the remaining items, the most impressive – including the Koh-i-Noor – were surrendered to Queen Victoria. Examples of arms and armour were sent to the Tower of London for display, while a selection of decorative arts – including Ranjit Singh’s golden throne – were deposited in the EIC’s museum (now part of the collections at the V&A).

However, the vast majority of the treasury was sold over a series of public auctions in Lahore in 1850. The contents of the sales encompassed the various luxury goods produced for all facets of courtly life. They ranged from tents to horse harnesses, state chairs, valuable gems, silks, shawls and crystal vessels, to richly decorated arms and armour – including a sword and scabbard containing 225 diamonds, 268 rubies, 381 emeralds and 517 small pearls, prepared by Ranjit Singh as a present to England.

The dispersal of the Lahore Treasury by the EIC has meant that many of the surviving items from the Sikh Empire – once owned by its nobility – have now lost their royal provenances. Items containing precious gems or metals are likely to have been dissembled and sold for their various parts, never to be seen again.

For more information on the provenance of the non-European arms and armour at the Wallace Collection, see Higgott, S., Sir Richard Wallace: Connoisseur, Collector & Philanthropist and Higgott forthcoming.