Guru Nanak’s successors initially enjoyed cordial relations with the ruling Mughals. However, within a century of his passing, the Sikhs were compelled to militarise against the threat posed by the newly installed Mughal Emperor, Jahangir (r. 1605–27). In 1606, the fifth Guru, Arjan (1563–1606), received the emperor’s rebellious son, Prince Khusrau, during his failed attempt to overthrow his father. For this gesture of goodwill, the Guru was swiftly imprisoned in Lahore. Following several days of torture, the Guru’s body was swept away while bathing in the River Ravi, never to be seen again. The Guru had already chosen his only son, Har Gobind (1590–1644), to succeed him as the sixth Guru.

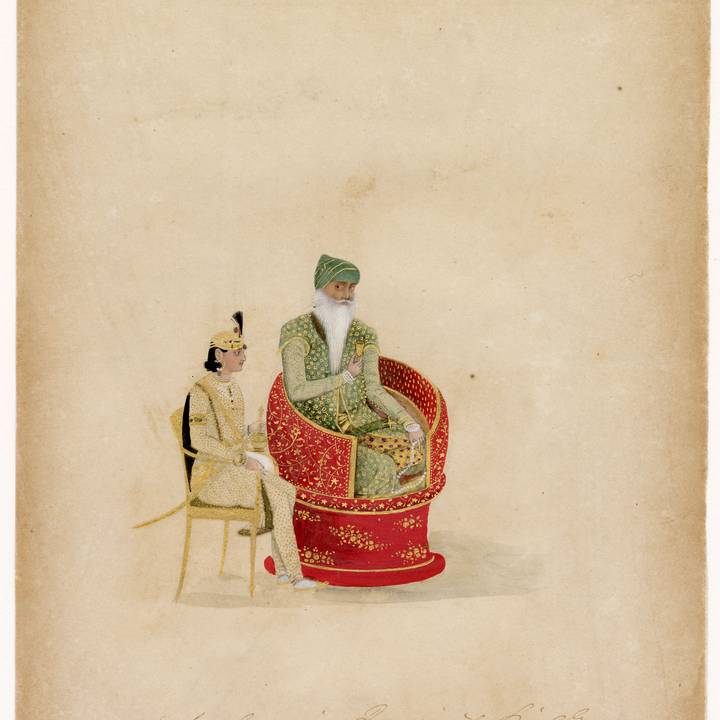

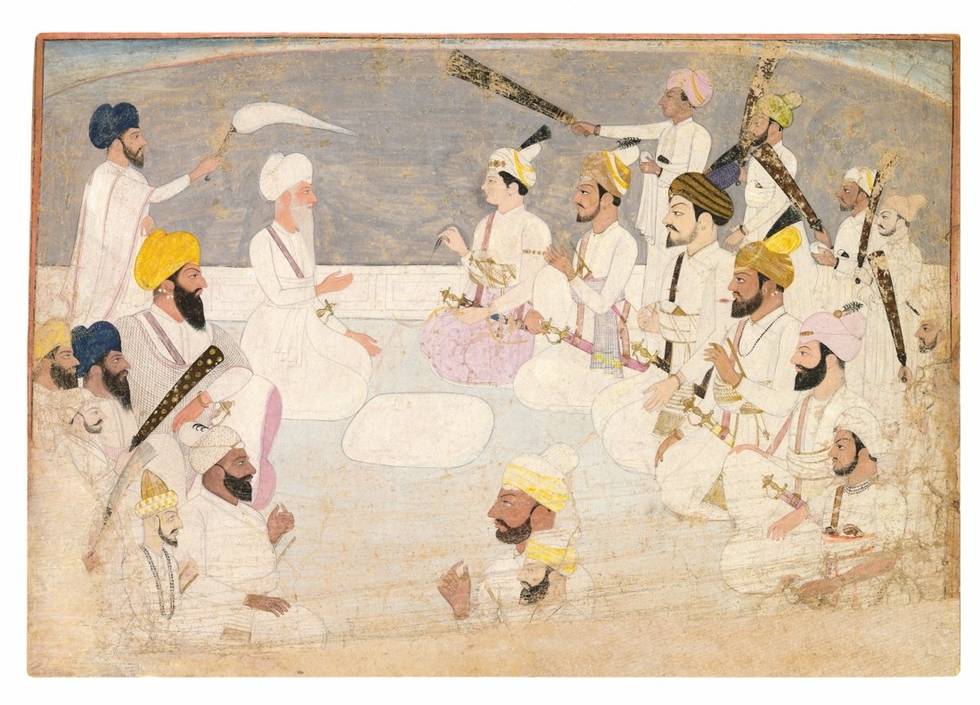

Sikhs gathered to mark Guru Har Gobind's formal accession ceremony. Before addressing the assembly, the young Guru called for some of his personal weapons including two swords that he named Miri (‘Of the World’) and Piri (‘Of the Spiritual’). When asked why he was thus armed, the defiant young warrior explained:

With one [Miri] we will take authority as king of kings. With the other [Piri], we shall achieve spiritual supremacy. All those who come our way seeking refuge shall be saved. Those who oppose us shall lose both their temporal and spiritual authority.

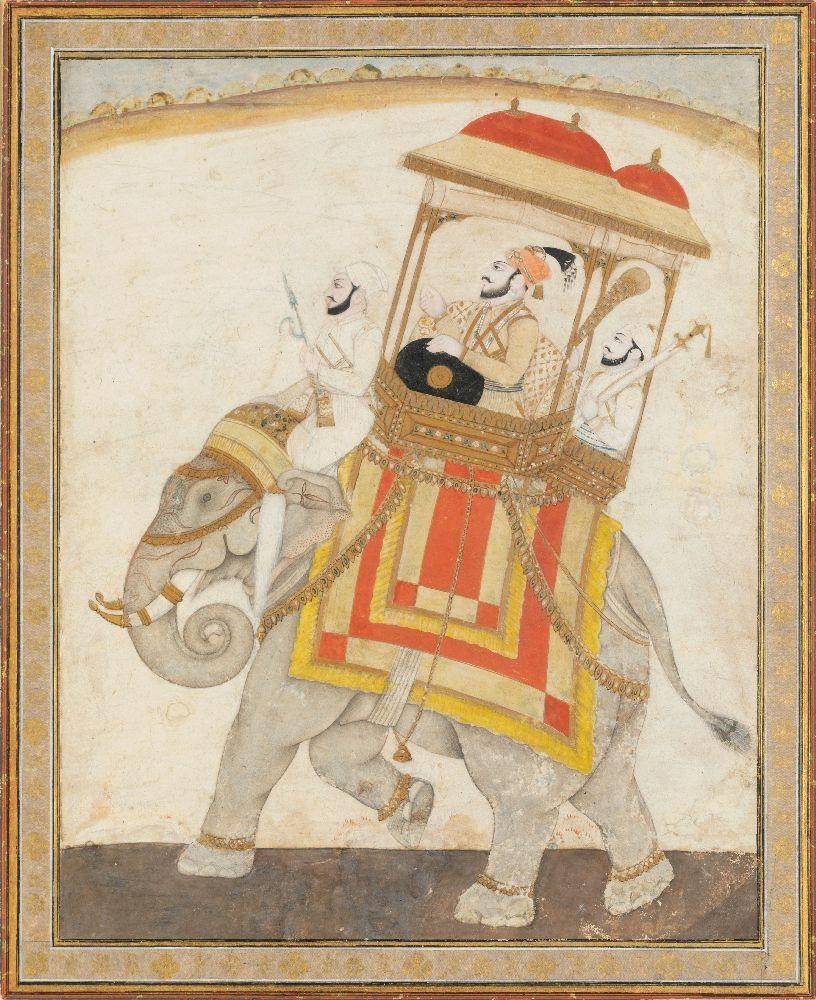

Guru Har Gobind immediately set about establishing a standing army to protect the nascent Sikh community. The need for such action was demonstrated when Jahangir later ordered the Guru’s imprisonment. He was eventually released and under his command, the Sikhs fought several battles against the forces of Jahangir’s son and successor, Shah Jahan (r. 1628–58).

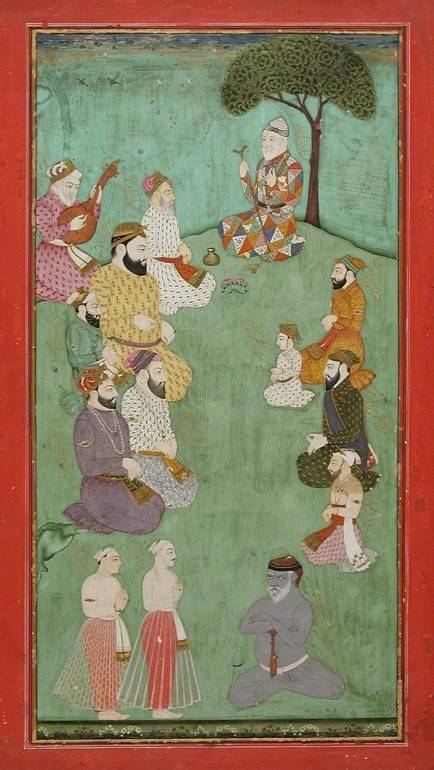

In 1644, the Guru passed leadership on to his 14-year-old grandson, Har Rai (1630–1661) who, like his grandfather, practiced daily military exercises. During Guru Har Rai’s tenure, a precarious peace prevailed across the Mughal Empire. However, in 1658, a state of chaos ensued as a war of succession began. The Guru offered military support to Dara Shikoh (1615–1659), a student of Indian mystical philosophy and a well-wisher of the Guru, who was pitted against his orthodox younger brother, the battle-hardened Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707). Being less experienced in the field, Dara eventually lost heart and so too the war. As the newly coronated Aurangzeb settled onto the famed Peacock Throne, he struck against his brother’s allies, among them the Guru, thereby beginning a fractious relationship with the Sikhs that would eventually lead to the execution of the ninth Sikh Guru, Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675).

To counter persecution, the tenth Sikh Guru, Gobind Das (1666–1708), guided his followers in a remarkable martial transformation from ‘sparrows to hawks’. This endeavour led to one of the key events in Sikh history, namely the formalising in 1699 of the Khalsa (‘Pure’) – a military and spiritual order of warriors, scholars and altruists – with a prophesy that the Sikhs would one day attain sovereignty. The Guru also instructed his adherents to adopt the surname ‘Singh’ (lion or tiger) and, in following them, he thus became Guru Gobind Singh.

Prior to his own passing in 1708, Guru Gobind Singh decreed that both the scripture, then known as the Guru Granth Sahib, and the Khalsa, were to be his successors. One of his final acts was to issue orders to the Khalsa to root out the Mughal Empire and seek justice for the murders of his youngest sons aged six and nine, who had been executed in the city of Sirhind a few years earlier.

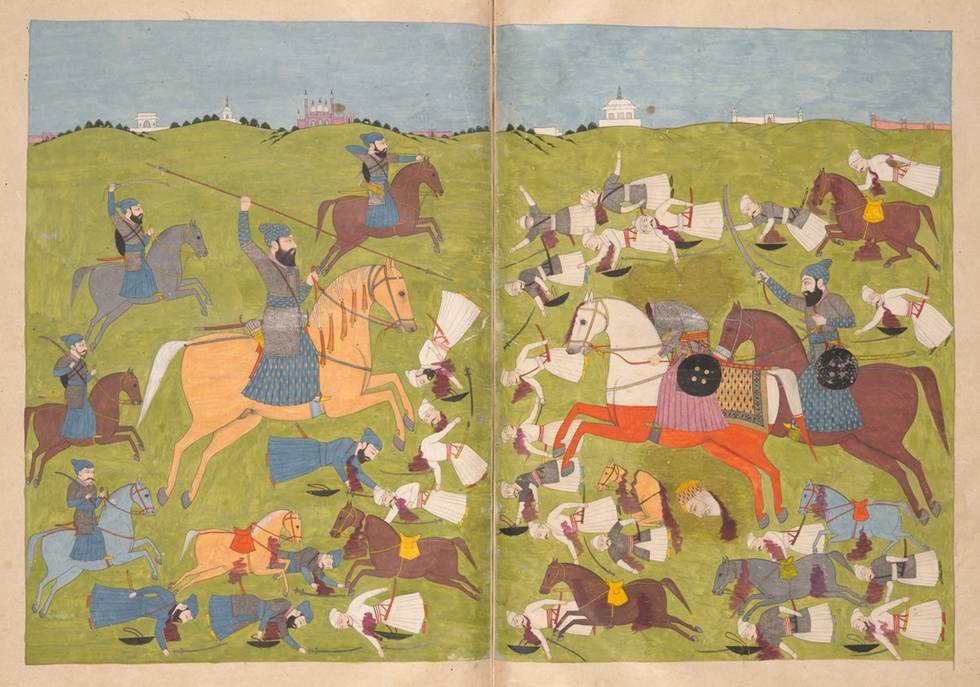

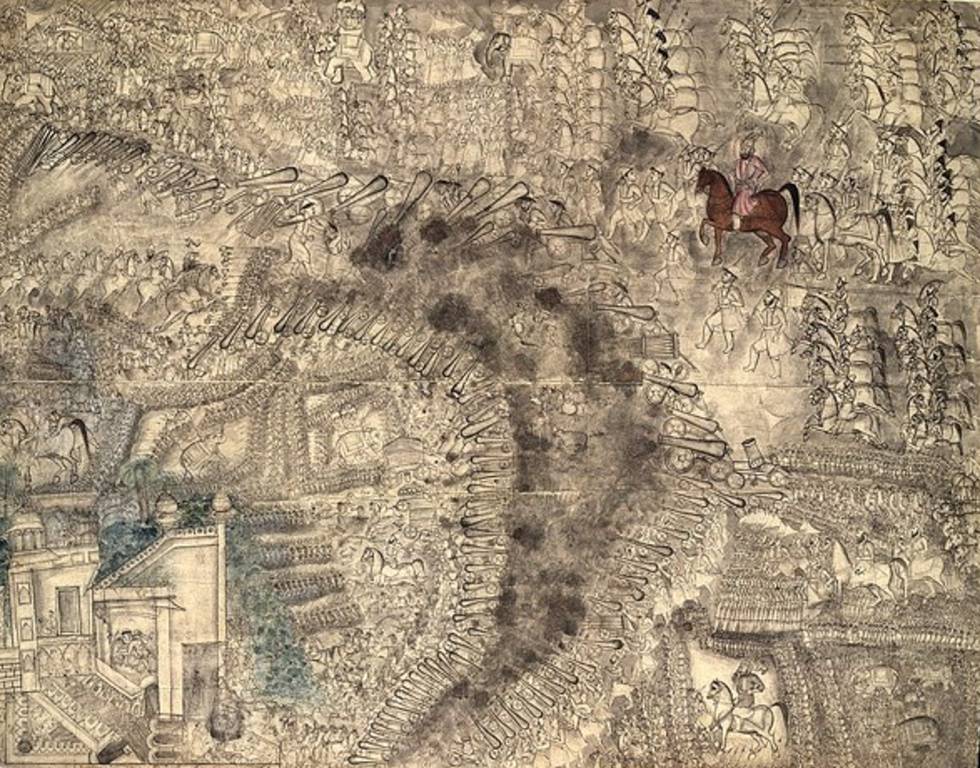

The man chosen for the task was the Guru’s field commander, a former holy man of the Bairagi mendicant order, popularly known as Banda Bahadur (1670–1716). Rousing an energised army from a discontented peasantry, Banda conquered town after town in the name of the Khalsa. When he swept into Punjab in 1709, his primary target was Sirhind and its governor, Wazir Khan (1635–1710). In 1710, the Sikhs avenged the Guru’s sons by taking control of this most important strategic Mughal stronghold, giving rise to the first, albeit short-lived, independent Sikh kingdom.

After three years of continuous warfare, Banda and his supporters were finally starved into surrender in December 1715. Several hundred Sikhs were sent to Delhi where they were executed alongside their leader. With the final stroke of the executioner's sword, the fate of the Sikh uprising, which had shaken the Mughal Empire but failed to uproot it, was sealed.

In the aftermath of Banda’s execution, the Sikhs that had evaded capture were forced to seek refuge in the haunts of Punjab's dense jungles, impenetrable swamplands and rugged mountain passes. For the next two decades, the Sikhs operated clandestinely on the highways, looting merchants and convoys carrying the state's tax payments to the capital. They compensated for their low numbers by relying on speed and secrecy, undertaking long marches and attacking at dawn, dusk or under the cover of night. Their favoured prizes were arms and strong horses as these ultimately assisted them in striking back at the imperial government, thereby crippling their military and fiscal grip over Punjab.

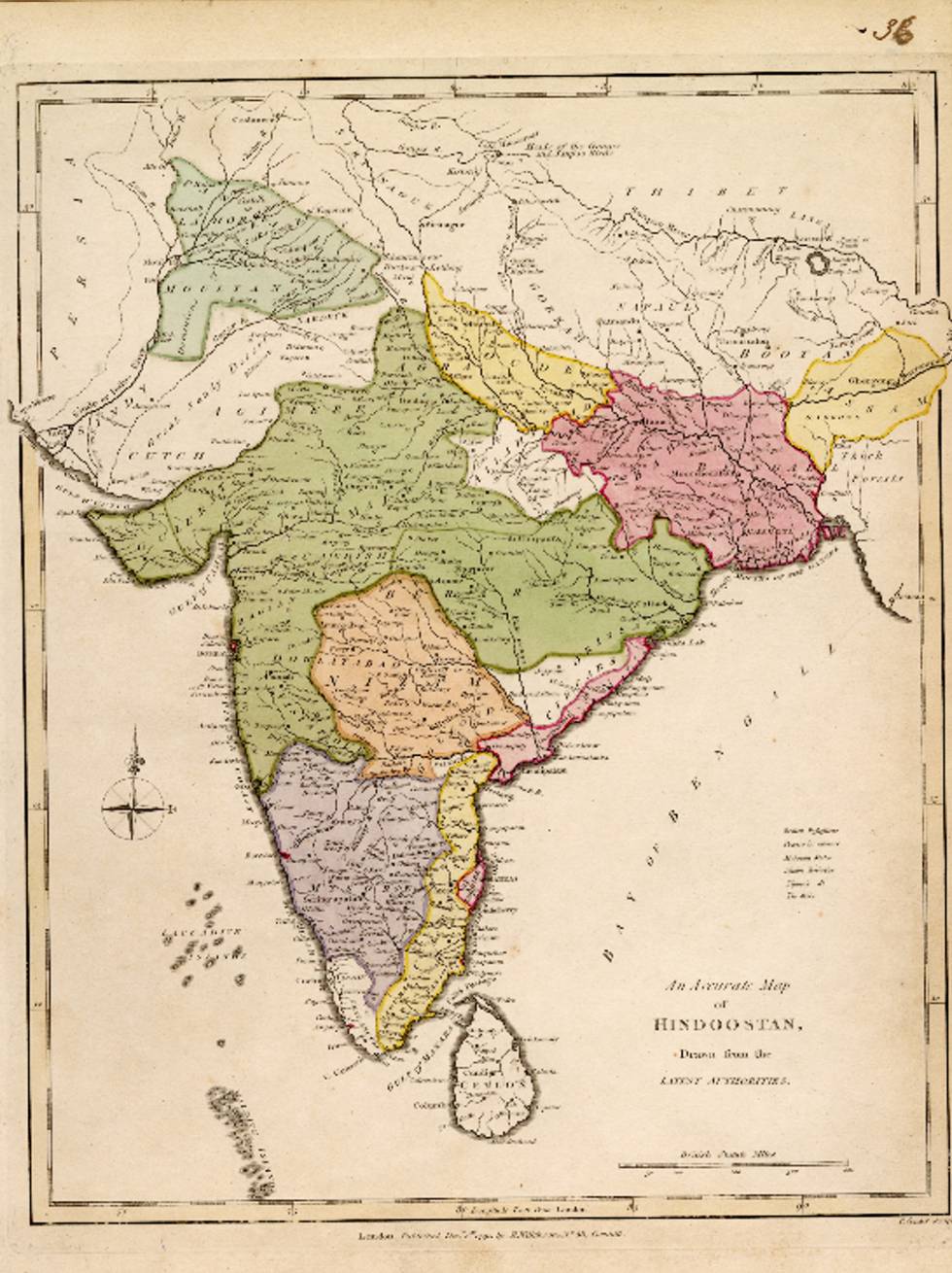

Proceeding decades saw successive Mughal emperors gradually lose control of a realm that was once a formidable, centralised military and political authority. As it weakened, invaders marched on the Indian subcontinent through the gateway of Punjab; first the Persians under Nadir Shah (1698–1747) in 1738, and then the Afghans under Ahmed Shah Abdali (1722–1772), who marched into the subcontinent no less than nine times between 1747 and 1767.

Sikhs organised themselves into a multitude of independent confederacies or misls (‘equals’). Towards the end of the 18th century, the territorial possessions of the Khalsa war-bands extended from Attock in the far north-west to down beyond Panipat into the very suburbs of Delhi.

These territorial gains brought about a semblance of peace. However, disputes broke out, and Sikh fought against Sikh.

Writing to a friend in London in 1785, the traveller George Forster (d. 1792) predicted the rise of a unifying Sikh leader:

Should any future cause call for the combined efforts of the Sicques [sic] to maintain the existence of empire and religion, we may see some ambitious chief led on by his genius and success, and, absorbing the power of his associates, display, from the ruins of their commonwealth, the standard of monarchy.

That ‘ambitious chief’ would be a five-year-old boy named Ranjit Singh (1780–1839).

This article was written by Davinder Toor, co-curator of Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King.